- Home

- Janice Marriott

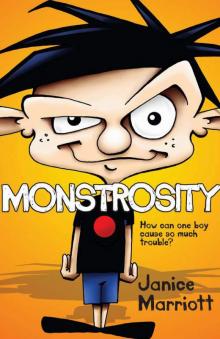

Monstrosity

Monstrosity Read online

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Green Slime Dinner Time

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

The B4 Battle

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

The Big Bug Blast

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Alien on Wheels

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Copyright

About the Publisher

Green Slime Dinner Time

1

It all started on Friday night when the phone rang. I answered it. It was some giggly girl, probably from my sis’s class. ‘Yes, that’s right. One teenage girl. She’s raising money for her favourite charity, an acne-cream product. She’ll do any jobs at all—cleaning toilets, writing other kids’ homework. $10 a job. I’m her…er…project manager. Think about it. Phone me back. Bye.’

I hadn’t expected anyone to phone home, but I had hacked into my sister’s Bebo page: word was obviously getting around.

Ring, ring!

‘Hello. Fabulous Fundraisers Limited here.’

‘Could I speak to your caregiver?’ This new voice sounded the way damp stone would sound if it could talk.

‘Caregiver! We don’t have those here. Just uncool old parents.’

‘Get me one of your parents. Now!’

I shouted as loud as I could. Mum and Dad were dozing in their big puffy chairs in the sitting room, just about one arm’s length from me.

Dad woke up and fought the spread-out newspaper off his face. Mum took the phone. Mum said lots of stuff into the phone about making sure I wouldn’t continue this cyber-bullying again. Then she put the receiver down very gently and whimpered, ‘Monster’.

Because of that small trick, I was chucked out of home. ‘Off to Aunt Mildred’s with you,’ they said. For a whole week—Sunday to Sunday. Just because I’d hacked into my sister’s Bebo page.

You’d have done the same if she was your sister. And my family should know me by now: playing tricks is what I do best.

By the time I arrived at Aunt Mildew’s dark house, on the edge of a forest in the middle of Nowheresville, I was hungry. I wanted to rush in, swing the fridge door open, grab the milk, and drink it straight from the box before I died of starvation. It was dinner time. Sunday dinner.

I stood on a creaky veranda, staring at a dimly lit door-knocker of a dog’s head, all bared fangs and pulled-back lips. This was harsh punishment for one small trick.

I lifted the evil knocker on the door.

‘Grrrrrrrrrrr!’

No one had warned me about Bloat, Mildew’s dog. He was shaped like a wide-bodied jumbo jet, except that he had no wings. He stopped growling and lunged at me, swinging his tail. I got suffocated by his foul-smelling breath. I moved back. Bloat whisked his top half around to bite his own backside hard, over and over again. Fleas. He shook himself. A cloud of dust, fleas and hair floated straight up my nose.

‘AAAAAAchoooo!’

I didn’t like Bloat.

The door creaked open.

‘Hello, Monster.’

My real name’s Brewster, but they all call me Monster because I play tricks on people all the time. Well, not all the time. I took one look at Mildew’s wrinkled, yellow face with the eyes in sockets so dark I couldn’t see them. I decided not to play a trick on old Mildew right away. Better be polite, wait a couple of hours, do a couple of nice tricks, then we’d all loosen up. Well, that’s what I thought.

‘Off with you to unpack and wash. Then we’ll see about a little dinner, shall we? You sound as though you’re getting a cold. Greens will fix that.’

I groaned. Bloat howled. Mildew smiled a slow, evil smile.

I walked in. How could I have known the horror that waited for me inside?

2

Plonk! I sat at the dining-room table. My stomach was gurgling so much I could hardly hear Mildew doing the ‘Howz’ questions. You know, those questions crusties always ask you:

‘Howz your mother? Howz your father? Howz that beautiful sister of yours? Howz school?’

I used four different words to answer the four questions. Fine. Great. Dead. Cool. Mildew didn’t listen to my answers, though. Or maybe she never liked Sis.

Where was dinner? Hurry up, rumbled the Great Grumbling Stomach Grabber inside me. Then it clawed at my insides, grabbing folds of my under-used stomach and knotting them up.

I looked around the room. On the mantelpiece was a photo of the man Mildew had married. Fred. He’d died years ago. Probably starvation. He had curly hair springing away from his head, which made him look like he was holding a live electric cable.

I noticed Mildew had rough, curly hair like a tangled fishing-line. I looked at Bloat. He was drooling and dribbling from saggy, black lips. He had wiry, curly hair and looked like something you clean the saucepans with.

I was surrounded by curly hair.

Plop! Mildew plopped lumpy stew onto two plates. She put the lid back on the pot. In front of her were two more pots with lids on. My Great Grumbling Stomach Grabber tightened its grip.

Mildew slowly took the lid off one of the mystery pots. Clouds of steam and…mashed potatoes. OK. I liked them. I’d survive after all. I’d find ways to play tricks and…

She took the lid off the third pot. Another cloud of steam. Then I could see glistening, round…meatballs? No. They were greenish. Whitish. Sticky-looking. Eyeballs? Surely not. Suddenly I knew: they were Brussels sprouts, my most unfavourite vegetable in the universe! Mildew spooned six of them onto my plate.

I would have to think of a trick very, very quickly.

Brussels sprouts for dinner meant only one thing. A fight. A big fight, between two stubborn opponents.

At one end of the table was me, Monster, the great trickster, with a burning hole in my stomach. I could eat all the sausages at the scout barbecue. I could eat a whole packet of Mars bars out of the supermarket shopping before Mum noticed they were missing. But I couldn’t, wouldn’t, eat Brussels sprouts.

At the other end of the table was Mildew, who believed boys should eat up everything on their plates and that greens were good for you. It was a standoff.

‘And I want them all eaten up. Make your hair curl, they do,’ Mildew thundered down the table.

‘Don’t want curly hair,’ I managed to say out of a dried-up mouth.

‘Hrrrump!’ Mildew said, like a horse snorting through rubbery lips.

We began to eat. I nibbled around the mashed potatoes. I bulldozed a carrot into the sticky gravy, then I covered it in potato, like a cloud on top of a distant plane in the sky. The carrot and potato flew into my mouth. I clamped my teeth on it, sucking in the gravy, spilling not a drop. The gravy coated my tonsils, then drizzled down my parched throat.

‘Wheeeeeem!’ I whistled a jet plane through my teeth as another airborne carrot and potato took off towards my mouth.

‘Stop playing with your food!’

Soon all that remained on my plate were six sprouts. I lined them all up.

&nbs

p; Hi, I said to them. I name you Splodge, Soggy, Squelchy, Slimy, Oozy and, er…Nameless. I will not be eating you, any of you, ever. Splodge, you look like something that a horse has coughed up and spat out. And you, Nameless one, you look like eyeballs of the very dead.

‘Aunt, what’s a name for the way eyeballs of the very dead look?’

‘Glaucous.’

I rolled them across the plate.

‘Stop playing with that food!’

I wasn’t playing with my food. I was playing for time, waiting for a trick to form in my starved mind.

Mildew got up and stood over me, watching. Did she know I was the master trickster of the universe?

‘Aunt, there’s a fly sitting on the custard cooling on the windowsill.’ Mildew’s bloodshot eyes didn’t move. Nor did her head. Nor did any part of her except her thin lips.

‘Eat. Those. Sprouts.’

I felt like crying. I slowly raised Splodge, opened my mouth wider than I did at the dentist, and forced the sprout inside. But then something in the back of my throat came down, something like a roller door on a garage, something that fell down, clang, and would not let anything be swallowed.

The sprout sat on my tongue, bleeding hideous sprout juice. A squillion taste buds examined it, shrivelled up, and sent pain signals to my brain. Sprout smells, like cat sick, crept up the back of my nose.

I rushed for the back door and vomited on the doorstep.

Mildew was not pleased. ‘No pudding,’ she said. ‘Clean up the mess.’ She picked up my plate with the five remaining sprouts, marched down the hall and into the dark kitchen. She called back over her shoulder.

‘You’ll eat these sprouts, Monster. They’ll be on your plate tomorrow, and the next day, until they are all gone.’

Urgent, major trickery was called for. I went up to my room to think and think. Mildew was mean. And not just mean. She was creepy, too. And how come, each creak of the stairs asked me, how come she knows about dead eyeballs?

3

The next afternoon, Monday, I was walking around the house planning a sprout-disappearing trick that involved sawing holes in the dining-room floor, when Mildew told me to take Bloat for a walk. I’d never walked a dog before.

I looked at Bloat, who was sitting on the veranda.

‘Here’s his lead. And a plastic bag.’

‘What’s the plastic bag for?’

‘To clean up after him,’ said Mildew.

Clean up after him? What did that mean? How could a dog make a mess? It wasn’t like they bought takeaways.

We started off down the road. Bloat pulled on the lead and sniffed every lamppost and bush, and cocked his leg on letter box after letter box. Then he crouched down, with his bottom near the ground. What if he did a steaming poo right outside someone’s gate? Then I realized why I had the plastic bag.

No! I yanked him up. I quickly stuffed the plastic bag into someone’s letter box. There was no way I was going to scoop up a slimy, fresh dog turd and then carry the ponging plastic bag around until I found a rubbish bin or until I was dive-bombed into unconsciousness by blowflies. Not me, Monster, the great trickster.

I turned around and headed for the forest behind Mildew’s house. I came to a sports ground where a league match was on. I sat down outside the changing room and let Bloat off the lead. I hoped Bloat would go and play with someone else, or just go off and do his own thing. That way no one would know he was with me.

I settled down to a few minutes of deep thought about the Brussels sprouts problem. There was a space under Mildew’s house. I could crawl under and drill a hole in the dining-room floor—a hole big enough for a Brussels sprout. Or I could drill a hole through my plate and the table so that I could drop the sprouts through to Bloat. If I had a drill. Or maybe I could hang a plastic bag around my neck under my T-shirt?

‘Hey!’

The league players had stopped playing, and were standing on the field looking furious. For some reason they were looking at me. Why me? I hadn’t—

Then I saw Bloat. He was crouched down in the middle of the field—I knew what was happening.

The biggest of the guys yelled at me: ‘Whatyergonna do with that crap, eh?’

I was brave. I walked up to the players. A wall of folded arms, like a huge twisted rope, was all the way around me. I had to do something fast, otherwise the guys might use me as the ball for the rest of the game.

I dragged my jersey over my head—it was a mohair one that Mildew had spent a lifetime knitting—and mopped the mess up into the jersey. It stuck to the mohair real well. Then I slunk off the field. Bloat waddled off after me. The guys all laughed. The game started again. It was my darkest hour.

Carrying the jersey at arm’s length, I walked further and further into the dark forest. It was winter. The trees dripped water down my back. The puddles were oily, and had rubbish in them. The shadows on the ground started mixing together. Darkness was coming. I came to a big river. It was too big to cross: I’d have to turn around and find my way back, somehow.

First, I threw the stinky jersey into the river. It got caught on a tree root. I threw a stick after it, then bombarded it with pine cones until it sank. A branch cracked behind me. I whizzed around, and there, watching from a little patch of pink sunlight, was a woman. She was wearing a cloak and a hat like a witch.

‘Hi,’ she said. ‘Long walk?’

I said nothing.

‘Want a drink before you go home?’

I still said nothing. After all, you’re not meant to talk to strangers.

‘And a bite to eat?’

To eat! ‘Depends,’ I said.

‘On what? I’ve just made a cake.’

She turned and I followed. Bloat came, too.

Her tiny house was hidden behind a huge tree which had a few jigsaw-puzzle-shaped leaves and a twisted trunk. There were cats every where. Bloat ignored them.

I wasn’t very fussed about whether the witch was bad or not. What I wanted to know was whether she was as bad as Mildew—and was she any good at cakes?

She told me her name was Sylvie, while she put a teapot on the table along with three cups and saucers, bright red and green, with blue insides and stars on them.

‘Who’s the other cup for?’

‘My daughter. She works in the shopping centre. Should be home soon. It’s nice to come home to a cup of tea and something to eat, isn’t it?’

We had apple cake with raisins in it, a sour cream filling, and icing on top. It was nine out of ten.

‘What were you thinking about when I saw you?’

Had she seen me chuck the jersey into the river? If she had, she didn’t say. Mildew would have fired questions at me like a firing squad, and they would all have been about what I was doing, but never about what I was thinking.

‘I was inventing survival tricks in my head.’

‘You studying bush craft?’

‘I’m surviving my aunt’s cooking.’

‘You’re staying at Mildred’s, aren’t you?’

I told her about the Brussels sprouts in the Tupperware container, glowering at me through the misty plastic, waiting on a shelf in the fridge for the next dinner, and then the next, and then the next…or until I had died of starvation.

‘Oooh, I shouldn’t think you’ll die of starvation,’ she whispered.

‘She reckons sprouts make your hair curl. They don’t, do they?’

‘Who knows?’ She smiled right into my eyes. ‘Have some more cake.’

‘Just a small piece.’ I decided to be polite. I wanted to be invited back. She cut me a large piece, and I told her about my plan to drill a sprout-sized hole in the dining-room floor, cover it with the chair, and make sure I wriggled the chair into a different position when I was eating.

‘But I don’t have a drill,’ I said.

After I’d eaten all the cake, she stood up.

‘I’ll drive you back because it’s dark. Your aunt will be worried.’

&

nbsp; ‘Not her.’

I didn’t want to be driven home. I wanted to go through the forest, dropping cake crumbs from a ginormous cake as I went. That way I wouldn’t starve on the walk and I’d be able to find the food goldmine again, in hunger emergencies.

‘And maybe you could use this, next dinner time.’

She opened a large wicker basket and took out a wig. She winked. It was a wig of very curly hair.

4

Mildew threw a major spaz when I got home. ‘Where were you? Did you know what time it was? Why didn’t you phone? If you’re not here for dinner in future, I’ll report you as a missing person. I have my responsibilities to your mother, you know.’

I hate people with responsibilities.

Mildew went into the kitchen.

There was one thing wrong with being so late. I hadn’t had enough time to work out a sprout-disappearing trick for today’s Battle of the Brussels Sprouts. I didn’t have a drill. I was about to sit down at the end of that long table, defenceless.

Then I remembered Sylvie’s wig. I pulled it out of my pocket. It was the uncrushable sort. I put it on my head and jammed my cap on top of it. I didn’t plan to reveal my secret weapon until the heat of battle.

Mildew brought in a pie. ‘Parsnip pie,’ she announced.

Parsnips. What were they?

She cut into the pie. It was all white and yellow and runny in the middle. Inside it were things that looked like the cooked legs of cats, or maybe dogs.

She speared one. ‘Parsnips,’ she said.

On the table, as well as the wobbly pie, was the Tupper-ware container with the five sprouts glowering through the plastic.

‘You are not getting down until you’ve eaten one,’ Mildew said. ‘Greens keep you regular.’

I felt my pulse. De Dah De Dah. It seemed regular to me. I wasn’t dead, anyway.

She handed me my plate of wibbly-wobbly parsnip pie and one cold sprout with drops of what looked like sweat all over it.

Hi, Soggy. You are about to be put out of your misery.

I shivered while I forced the pie into my mouth.

‘Where’s your lovely jersey?’

‘Dunno.’

The room was freezing.

Monstrosity

Monstrosity